This Mainichi Shinbun photo captures the feel of the Friday night demos perfectly. I’m somewhere in the middle of all those people, sweating and hollering.

It’s Friday night again in Nagata-cho, Tokyo’s government district, and I’m literally a human sardine (this analogy means more to Americans and Europeans, who eat their tightly packed sardines from a can. Most Japanese, who don’t, draw a blank). Having arrived on time for the weekly demonstration outside the Diet Building, I’ve been swiftly and politely herded into a narrow sidewalk space where the street-view is blocked by a line of enormous empty busses. And there I stand, hollering “Genpatsu, Hantai!” ( We Oppose Nuclear Power! ) for the next two hours; can’t move, can’t see a darn thing, and the two friends I dragged along (their first time) are dying of mortification and refusing to wave the anti-nuke placards I thoughtfully provided for them. I know that one of them, Toshi, is dying to break free and head for the nearest izakaya to get a cold beer. “Too bad for him,” I think smugly. “He’s trapped here, and it’s for his own good!” Toshi, I am sure, is wondering why on earth he agreed to come (out of curiosity, I suspect) and will have a few choice words for me at a later time. Mizue, on the other hand, is holding her placard chest-high and looks like she wants to yell, “Genpatsu, Hantai!” but can’t quite get the words out of her mouth. She might come back with me again.

The protesters around us wave a variety of signs: some reading simply “No Nukes!” , and others more specific: Work Toward a Peaceful World! Protect the Children! Love the Earth! Ditch the Prime Minister! Disarm, Now! Stop the TPP! Safer Food Standards! , etc. etc. The organizers of the Friday night demos have urged people to focus simply on the nuclear energy issue, but with so many anxiety-provoking related concerns, that has proved impossible. Blogger EX-SKF thinks the single-issue focus is a mistake, and I heartily agree. The average Japanese citizen has compartmentalized nuclear power for too long, neglecting (or refusing) to consider it holistically, in relation to a myriad of other issues that are now coming to the forefront. Since August marks the commemoration of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, today’s post will focus on nuclear arms rather than nuclear energy, in honor of those who died and those who survived. Some of the survivors–most are in their late seventies– bear physical scars and some are burdened with emotional scars, but none have been left unscathed. Here are pictures, drawn by survivors of the Hiroshima bombing, that tell the story as seen through their own eyes.

Now some people may believe that nuclear armament is a non-issue for this country. World War II ended with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; since then, Japan has been sworn to pacifism, according to Article 9 of the U.S-Japan Security Treaty of 1947, which reads, “….the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes.” It is also true that since the bombings, even the most conservative governments have followed the “three nuclear principles” prohibiting the production, possession, and introduction of nuclear weapons on Japanese territory. The average Japanese citizen is horrified by the thought of nuclear weapons, and the country as a whole is said to have an “allergy” to the subject, due to the lingering reverberations from the devastation inflicted by Fat Man and Little Boy.

Recent news , however, suggests that Japanese citizens who march for nuclear disarmament have good reason to be taking to the streets. Last Tuesday, AP news reported that certain conservative government officials and thinkers believe Japan’s pacifist framework to be outdated. They want to earn some respect in the eyes of their neighbors and show off their nuclear “capabilities” by continuing to maintain nuclear power plants, which develop the technology and provide the necessary fuel for atomic weaponry. “Having nuclear power plants shows to other nations that Japan can make nuclear arms, ” declared ex-defense minister Shigeru Ishiba, stressing that Japan needs to assert itself , using the potential threat of nuclear weapons as diplomatic clout. The same AP article claims that despite repeated denials by successive governments, a future nuclear arsenal has long been discussed “behind the scenes”. In related news, a recent AFP news article by Kyoko Hasegawa revealed that an expert panel of government officials is proposing to allow the US transport of nuclear arms through the country; again, this will presumably boost Japan’s image as a nation able to flaunt the protection of America’s “nuclear umbrella”. Lastly, those who read the newspaper closely are aware that the Atomic Energy Basic Act of 1955 was revised by the government last month to include “national security” as one of the reasons for possible use of nuclear technology. Given that Japan has one of the world’s largest stockpiles of plutonium (did you know that?) , these new developments have caused both anger and heartache on many levels.

Should the average citizen be seriously worried that Japan could develop a nuclear arsenal in the future? A recent guest article from the Plowshares Fund blog suggests that these fears are unfounded. Gregory Kulacki, an expert on nuclear weapons and global security representing the Union of Concerned Scientists, states that

“Japanese public opinion polls consistently register high levels of support for nuclear disarmament and strong opposition to Japanese nuclear weapons. The AP story fails to convey that the information now coming to light about Japan’s nuclear past reflects a strengthening, not a weakening, of Japan’s anti-nuclear credentials.”

Past discussions on nuclear matters were kept secret, he claims, out of fear of inciting “massive public protests”, and recent revelations of these discussions reflect the beginnings of a new transparency in government and media, which can only be seen as positive.

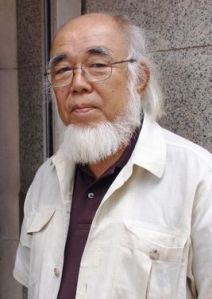

Nevertheless, there are those who fear for Japan’s future, and those who are incensed with conservative officials who promote nuclear power as a form of diplomacy . On August 5th, the day preceding the Hiroshima Peace Ceremony, the New York Times ran an editorial by Japan’s Noel Prize-winning novelist Oe Kenzaburou entitled “Hiroshima and the Art of Outrage“. The letter was part editorial (introducing some of the contradictions inherent in Japan’s publicly pacifist stance) and part personal, describing Oe-san’s own reaction to them. Stating that he feels deep disappointment in never having written a “big novel” about the victims of the atomic bombings, Oe-san seems to blame himself for not doing enough in the cause of peace. In his own words,

“…on the day last week when I learned about the revival of the nuclear-umbrella ideology, I looked at myself sitting alone in my study in the dead of night…and what I saw was an aged, powerless human being, motionless under the weight of this great outrage.”

Oe-san explains that his righteous anger takes the form of a “concentrated tension” that, although it may not result in a novel, could well be a form of art in itself. The image of an old man, alone in his study, rendered powerless by his own anger and holding in a peculiar form of tension is in itself a powerful image, and we must respect Oe-san for revealing himself so honestly as well as making a strong moral statement.

Outrage is essentially anger: righteous anger that can be empowering rather than crippling (Oe-san proves this himself, by turning out a tightly-constructed, moving editorial in spite of his protestations of helplessness). Let’s now move on to another story about outrage involving the former Mayor of Nagasaki, who was recently featured in the Asahi Shinbun. Serving as Mayor of the city from 1979 till 1995, Motoshima Hitoshi consistently opposed Japan’s history of imperialist aggression. A blunt and courageous speaker, Mostoshima-san went so far as to publicly state that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were an inevitable outcome of Japan’s agressive policies against its Asian neighbors, and that Emperor Hirohito must bear responsibility for the war. He received the Akizuki Peace Prize for his contributions to the antinuclear peace movement in Japan; he also received a bullet in the back in 1990 from a member of a rightist group who saw things differently. Motoshima-san survived, and remains unintimidated by his enemies. The ninety year old former official who was interviewed this past week stated matter-of-factly that he was neither stunned, terrified, or saddened by the nuclear meltdowns and ensuing chaos at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. He viewed the disaster as a “matter of course”, brought on by the use of a technology that should never have been utilized in the first place.

But wait: I was going to write about nuclear arms, rather than nuclear energy, right? Except that it’s not that simple. Many of Japan’s most respected thinkers believe that the two are inherently connected. Inseparable. Here’s how Motoshima-san sees the situation:

“The Fukushima disaster is bringing us to a new era, one in which all Japanese must confront not only nuclear weapons, but nuclear technology as a whole. As a Nagasaki citizen, I still want to believe that a nuclear-free world is not a dream vision. I can still say that we have a long way to go before we can view nuclear technology as a whole as an absolute evil.”

Motoshima-san’s words are echoed by an American poet who writes and speaks fluent Japanese and has recently published a photo book of keepsakes from the victims of the Hiroshima bombing. Arthur Binard, 45, grew up believing that the atomic bombings were necessary to hasten the end of the war and save the life of US servicemen. Travelling to Hiroshima in 1995, he re-imagined the situation through the eyes of the victims, who are called “hibakusha” in Japanese. Binard now firmly opposes both nuclear weapons and nuclear power as a form of energy. “The nuclear weapon and nuclear power plant are the same essentially, ” he says. “Nuclear fuel is inside, just with different containers. The story of Hiroshima is not something in the past. It’s a lens through which we can look at today’s world where nuclear damage has been spreading.” The former Mayor of Nagasaki would wholeheartedly agree.

The wrongness, ( the evil, as some would not hesitate to say) inherent in nuclear technology that so outrages anti-nuclear activists worldwide lies in its destructive potential. Given that nuclear power plants are controlled by man, and man is vulnerable, many citizens no longer believe that the benefits (prosperity) outweigh the risks (long-term damage to the environment and potentially to the the physical and mental health of adults and children, to name just two) of using nuclear power to slake an energy need that has not proven to be nearly as large as governments and the nuclear

industry would have us believe. Despite TEPCO’S claims to the contrary, a panel of experts in Japan has recently concluded that the multiple meltdowns were in fact, a “manmade disaster“, implying not an inconceivable act of nature, but an event caused and exacerbated by corruption, greed, mismanagement, incompetence, and lack of foresight. In short, the disaster was the result of collusion between central government, regulators, and nuclear plant operators. Following the “nuclear technology is evil” premise to its logical conclusion, the Daiichi plant should never have been built in the first place since its safety could not be guaranteed by men, who are inherently fallible. Thus the former Mayor of Nagasaki’s lack of surprise and grim sense of vindication after the meltdowns. Small comfort to be able to say, “I told you so! ” after a major nuclear disaster.

So what’s to be done to right the wrongness? For although many may still not agree that nuclear technology in itself is inherently wrong, few would argue that the misuse of nuclear power is not a crime. Well, “what’s to be done?” is the burning question these days, and the fact that ordinary Japanese citizens have begun to see themselves as part of the solution is progress in itself. Rather than saying, “Shikata ga nai” (It can’t be helped) , people young and old are hoping that things CAN be helped, and are speaking out instead of waiting for something to happen.

Cynics note that although the Friday night protests outside the Prime Minister’s residence attract steadily more participants, media coverage is still unpredictable at best. And the Prime Minister, who had promised to meet with organizers of the weekly rallies ( he had even set a date ) suddenly backed out and changed his mind, with no explanation. And there’s squabbling and back-stabbing going on even within the ranks of the rally organizers as well, as evidenced by some public conversations on Twitter. But still, the rallies are a source of hope and national interest. Although I am still not besieged by requests (“Take me with you! I’ll go to the demo, too!”), friends and family now express curiosity and support. If I lived in Tokyo, closer to the action, I’d have an army of friends riding the train with me to the government district. I just know it.

Former Keio University professor Fujita Yuko, called the “Lone Wolf Physicist” for his anti-nuclear stance dating back thirty years before the Fukushima disaster, recently told the Asahi Shinbun that Japan’s only hope lies in protest movements by citizens. “The fact that tens of thousands of non-partisan people are demanding a say means a turning point in Japanese democracy. I hope it will continue on so that it will prevent the government’s attempt to cover up nuclear damage.” So far, the movement is not only continuing, but gaining in momentum, in spite of the cynics. While the Prime Minister still remains in power and the central government’s official policy on nuclear energy (fuzzy at best) has not changed, citizens are certainly making government officials’ life both miserable and challenging. We make a big noise, require a massive amount of manpower (bad guys should be having a heyday in Tokyo every Friday, since the entire city police force and probably imports from surrounding prefectures as well seem to be concentrated in the government district, rather than guarding banks and jewelry stores), and are indefatigable as far as petitions, letters, and complaints. We have an awesome network and we use it. Best of all, we represent a broad swath of the population, and can not fairly be labelled as weird, extreme, or hysterical. On our side? We’ve got Oe Kenzaburou, Murakami Haruki, Miyazaki Hayao, Sakamoto Ryuichi, and Setouchi Jakucho….to name just a few. I, for one, know I’m riding on the right train, and feel certain that it’s not headed for derailment. Where it IS headed is anyone’s guess at this point, but to keep moving is the important thing.

Meanwhile, removed from the noise and clamor of the nation’s capitol, a group of Buddhist priests have just completed their “March for Life”. They share the same vision as the weekly demonstrators, but choose to express their outrage through prayer. Beginning last year, the priests have travelled the length of the country on foot, stopping at each and every nuclear power plant along the way.

Buddhist priests participating in the “March for Life”, making their way south to the Peace Ceremony in Hiroshima. (photo by Kiyoshi Inoue)

After making a plea to local officials of each host city for a nuclear-free future, they pray on the grounds surrounding the power plants and at the nearby waterside, as a ritual purification of the land which they believe has been desecrated. Their statement, which can be read online both in English and Japanese, is a clear indictment of nuclear technology, which they see as a violation of human rights. “It is a precept of Buddhism that you shall not kill other living beings, nor shall you make others kill, and moreover that the life of all sentient beings is precious and shall be nurtured. ” They believe that the use of both nuclear arms and nuclear reactors, by threatening the existence of life itself, must not be tolerated; those who were born in this era (they believe) must confront the crisis and bring the nuclear age to a close.

Public sentiment is with the priests, as was reflected in the twin peace ceremonies held in Nagasaki and Hiroshima this past week. Every year on the evening of August 6th in Hiroshima, paper lanterns inscribed with the names of those who died are set afloat in the Motoyasu River, in view of the Atomic Bomb Dome. This year’s event organizers reported the number of lanterns inscribed with prayers for peace or calling for an end to nuclear power generation outnumbered the number of lanterns inscribed with victims’ names. At the official ceremony itself, Mayor Matsui Kazumi of Hiroshima gave this strong and moving appeal for nuclear disarmament:

“Determined never to let the atomic bombing fade from memory, we intend to share with ever more people at home and abroad the hibakusha’s desire for a nuclear-weapon-free world. People of the world! Especially leaders of nuclear-armed nations, please come to Hiroshima to contemplate peace in this A-bombed city.”

He then extended his appeal, calling on the Japanese government to “establish without delay an energy policy that guards the safety and security of the people”. Mayor Tomihisa Taue of Nagasaki echoed this sentiment even more directly, challenging the central governement to “..set new energy policy goals to build a society free from the fear of radioactivity.”

It is worth noting that the hibakusha of both Nagasaki and Hiroshima consider the citizens of Fukushima to be fellow victims. Since the issue in Fukushima is long-term exposure to low-level radiation rather a direct and vicious atomic bombing that incinerated victims on impact, it could easily be said that the situations were completely different–that Fukushima citizens cannot be considered “true victims” of radiation exposure. Yet repeated interviews of elderly residents who lived through the bombings prove the reverse: hibakusha of Nagasaki and Fukushima fear for the future of Fukushima residents and consider them as fellow sufferers. Mayor Taue spoke for his constituents last week when he pledged, “We here in Nagasaki will continue to support the people of Fukushima, as it brings us great sorrow that every day they still face the fear of radiation.”

Atomic bombs and nuclear power plants: the same evil in a different package? Whatever you personally believe, for more and more Japanese citizens they are one and the same. In closing, let me quote from the closing section of Murakami Haruki’s now-famous anti-nuclear speech entitled “As an Unrealistic Dreamer”, in which he neatly and firmly ties together the two concepts:

“As you know, we, the Japanese people, are unique in having experienced nuclear attacks. In August 1945, US military aircraft dropped atomic bombs on the two major cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, resulting in the deaths of more than two hundred thousand people. Most of the victims were unarmed, ordinary people. Now, however, is not the moment for me to consider the rights and wrongs of this.

What I want to point out here is not only that two hundred thousand people died in the immediate aftermath of the nuclear bombing, but also that many survivors would subsequently die from the effects of radiation over a prolonged period of time. It was the suffering of these victims that showed us the terrible destruction that radioactivity has brought to the world and to the lives of ordinary people.”

Murakami continues, with his own assessment of what Japan’s future should have been, and how the nation can begin to repair the damage it has inflicted upon itself:

“We should have made the development of non-nuclear power generation the cornerstone of our policy after World War II. This should have been the way to assume our collective responsibility for the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Japan, we needed strong ethics, strong values, and a strong social message. This would have been a chance for the Japanese people to make a real contribution to the world. We neglected to take that important road, however, preferring to pursue the fast track of “efficiency” in support of our rapid economic development.

As I mentioned earlier, we can overcome the damage caused by natural disasters, however dreadful and extensive they might be. And sometimes our spirits may grow stronger and more profound through the process of overcoming. This is most certainly something that we can achieve.

It is the job of experts to rebuild broken roads and buildings, but it is the duty of each of us to restore our damaged ethics and values. We can start by mourning those who died, by taking care of the victims of this disaster, and by nurturing our natural desire not to let their pain and injuries have been in vain. This will take the form of a carefully crafted, silent and painstaking endeavour. We must join forces to this end, in the manner of the entire population of a village that goes out together to cultivate the fields and plant seeds on a sunny spring morning. Everyone doing what they can do, all hearts together.”

Murakami, who delivered this speech last year in Barcelona, is currently lecturing and writing at the University of Hawaii, but I feel certain that he’s cheering us on from across the ocean at the Friday evening protests in Nagata-cho. It’s our own attempt at restoring our damaged ethics and values and, whatever minor disagreements might incur, our hearts are all together.

Thank you for reading and reflecting, and stay tuned for the next chapter.