ZERO NUCLEAR POWER BY 2030’s: OFFICIAL GOAL!! ….read the headline of my Japan Times morning edition on September 14th. This had probably been announced on the previous evening’s news as well, but I had been out walking with my neighbor in an attempt to work off a too-large portion of my husband’s delicious fried rice. My immediate response to the morning headline was , “hmmm….what’s up? “, and I dug in to the article without delay. Note that my immediate response was not, “Wow! That’s awesome!”—not by a long stretch. For one thing, protestors in Tokyo are calling for an end to reliance on nuclear power NOW, which could be achieved simply by shutting down the two reactors at the Oi Power Plant in Fukui Prefecture. Zero nuclear power by the 2030’s?? That would give the government plenty of opportunity to keep the Ooi reactors running and re-start others in the meantime. So I read the article calmly and objectively, and was not surprised to discover the clause at the end added by the Prime Minister: “It is extremely hard to predict how things may develop in the future and we should make sure that we are able to take a flexible approach.” Flexible, meaning “Well, we’ll TRY to keep this promise. But it may not work out, so please understand, okay?” And to add insult to injury, the article

Citizens demand the closing of Fukui Prefecture’s Monju Fast Breeder (seen in the distance). Photo by KYODO News.

made it very clear that the government intended to continue the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel, and did not plan to give up on the Monju fast-breeder (a prototype reactor that theoretically will run on reprocessed uranium and plutonium. The reactor has been plagued by accidents and cover-ups, and currently sits idle; it has actually only produced a single hour’s worth of electricity since its completion, which involved four decades of work and an appalling amount of money), scheduled to come on-line in 2050. Hmmm…..no nuke plants at that time, but the country would still be producing a stockpile of uranium. And for what purpose?? The potential for nuclear armament could not be separated from the equation.

On September 15th, the Asahi Shinbun published an article on the Zero Nukes announcement, asking the question, HOW FIRM IS THE NO-NUKE POLICY? IT CONTAINS GET-OUTS, CONTRADICTIONS. Asahi made no bones about calling Noda’s announcement a “hollow promise” as well as a shameless plug to win the support of ordinary voters (good luck with that). From this article, I learned that a Legal Requirement Clause, added to the policy by minister Motohisa Furukawa, had been struck out at the last minute, meaning that in fact local and central governments were not bound by law to effect the policy at all. The whole declaration was, in fact, a non-binding promise thrown out in a desperate attempt by the government to save face (again, good luck with that).

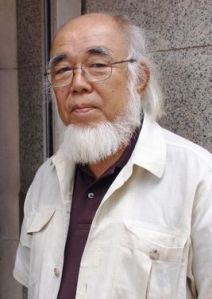

Yonekura Hiromasa, Chairman of Japan’s Business Federation, had plenty to say about the Zero Nukes by 2030 announcement. (photo from Asahi Shinbun files)

Let me now skip ahead: Just five days after the original announcement, the Asahi Shinbun ran another article with this headline: JAPAN’S NO-NUKE PLEDGE IS ALREADY FRAYING AT THE EDGES, followed by the next day’s Japan Times annnouncement CABINET FAILS TO OK NEW NUCLEAR STRATEGY, describing the “shocking reversal” that took place in a matter of six days. The entire policy had been watered down to nothing due to opposition from both the US and the Japanese Business Federation (Keidanren). This was only “shocking” for those who believed that the government was seriously committed to its own policy, however, and since many folks wanted a break with nuclear power immediately (rather than 18 years down the road), they had not been terribly excited about the announcement in the first place. Still, even for cynics, it was a disheartening and disappointing week. What an embarrassing excuse for a government.

Yet although the government seems like a bundle of contradictions and broken promises to citizens of Japan, citizens abroad have differing perspectives. Let’s jump now to Vietnam, a nation which, with the assistance and “know-how” of both Russia and Japan, is about to go nuclear. In spite of the Fukushima disaster, the Vietnamese government plans to honor their contract with a Japanese firm to build a nuclear power plant, and in fact, preparations are already underway. While the Noda administration waffles and stumbles before its own citizens, it is “leading the way” with confidence in Vietnam, where residents believe that 1) the nuclear industry is safe and trustworthy, and 2) Fukushima was something unfortunate, but unrelated to their own situation.

Vietnamese students analyzing radiation samples at the Hanoi workshop (photo by Chau Doan, for NY Times).

Japan lobbied aggressively to win the contract to build a nuclear power plant in Vietnam. As critics correctly charge, Japan and other nuclear powers are now desperate to sell plants to developing nations, since Fukushima has destroyed the dream of a nuclear renaissance in advanced economies. And in this case, since Vietnam does not yet possess the technology or even the know-how, Japanese experts must train a generation of young Vietnamese who hope to become nuclear engineers: future researchers, operators and managers of the nuclear power plants that the government hopes will revitalize the country. A New York Times article from this past March details a workshop held in Hanoi, sponsored by members of the Japan Atomic Energy Agency; in a Japanese-built research lab, Japanese specialists held a ten-day workshop for a group of twenty young and eager Vietnamese students, described as “Radiation Physics 101”. Radiation Physics in ten days?? Is that something like the old cassette tape I used to have entitled, “Ten Classics in Ten Minutes”? I loved that tape: you got a synopsis of Moby Dick, Great Gatsby, Gone with the Wind, and seven other novels, TRULY in ten minutes, complete with funny voices and sound effects. At any rate, the Vietnamese government intends to move fast enough to have a sufficient number of qualified experts to manage the first nuclear reactor (scheduled for 2020) and to build and operate at least nine more by 2030. I don’t know about funny voices and sound effects.

And I am not the only one who thinks this all a bit too hasty. According to the same NY Times article, both Vietnamese and foreign experts have already expressed concern that this leaves “…. too little time to establish a credible regulatory body, especially in a country with widespread corruption, poor safety standards, and a lack of transparency, ” and that “…the overly ambitious timetable could lead to the kind of weak regulation, as well as collusive ties between regulators and operators, that contributed to the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan last year.” That sounds like a pretty sound assessment to me.

Still more disturbing was an article I found in the Asia-Pacific Journal entitled “Japanese Nuclear Power Comes to a Vietnam Village” (under the “What’s Hot” tab) . It’s an essay by photo-journalist Kimura Satoru, who journeyed to the village of Tay Anh, in south central Vietnam, where the first of the nuclear power plants is scheduled for construction. The village, as Kimura-san describes it, is much like some of the coastal villages in Tohoku: sustained by both fishing and farming, and rich in wildlife and natural resources. My daughter would be interested in the rare sea turtles that come onto the sand to breed and lay eggs. Seven hundred households make up the village, and their inhabitants will be re-located to an area two kilos away, as early as 2014. “It can’t be helped as it’s for the development of the country,” says a farmer interviewed by Kimura, and this seems to be the general attitude of other residents as well.

Kimura-san relates the story of village residents who were invited to fly from Vietnam to tour a Japanese nuclear power plant in 2010; they returned suitably impressed and convinced of the safety of nuclear energy, and were instructed to relay what they had learned to other villagers. The following year, meltdowns at Fukushima naturally caused anxiety abroad, and a Japanese delegation was dispatched to Vietnam to assure villagers that Japan had learned from its mistakes and that nuclear power was, in fact, as safe as ever. Kimura is convinced that residents of Tay Anh have accepted this explanation, as villagers he spoke with showed little evidence of fear or distrust regarding the forthcoming construction project that will overtake their homes and farms in less than two years. Here’s the situation in the journalist’s own words:

What I see among Vietnamese in the midst of nuclear power plant construction is the impossibility of their learning about nuclear power. Above all, they lack both consciousness of the issues and sufficient information. The reason the Tay Anh villagers are not negative about nuclear power is not that they actively endorse its safety. The reason is that no negative information is disclosed to them. Their trust in the Japanese people’s high technical ability seems to influence the residents’ consciousness of nuclear power. Thus I unexpectedly heard the safety myth about nuclear power in Tay Anh village. It floated among villagers like a ghost that has no substance.

And that’s the bottom line to me: in this small Vietnamese village there seems to be a myth of safety and security associated with nuclear power, combined with a dearth of information. Ordinary citizens have a basic right to know about the proposed facility–in detail– and to have a say in where, how, or even IF it should be constructed. That’s only natural, since it’s their own health at stake. And the environment does not seem to have a spokesperson at all…is there anyone pleading the case of the sea turtles? Or the nearby National Park that could become nothing more than a cesium repository? So far I’ve heard nothing, but my ears are open.

Reporters and Tepco workers accompany Environmental/Nuclear Minister Hosono Goshi on a tour of Fukushima Daiichi’s battered number four reactor in May, 2012.

I do not live in Vietnam, and it could be said that whether or not their government builds a nuclear reactors is none of my business. Yet since Japan is behind the construction and “education” process, I cannot help but have an opinion. In this case, my message is to the Japanese government: “Clean up your own mess before you start a new one!” It’s as simple as that, and I’ve written about it in a previous post. With new revelations seeping out insidiously on almost a daily basis (this week’s shocker revealed that the town of Futaba was essentially blanketed in radiation even before the first hydrogen explosion occurred) and large pieces of machinery tumbling into the fuel pools of the damaged Fukushima Daiichi reactors (a thirty-five ton machine was discovered submerged at one point. This week, a large steel beam tumbled in) , it is clear that the crisis in Fukushima is ongoing and that nuclear power will never be completely “safe”. We have no business selling a form of energy abroad that our own citizens have solidly rejected and that has poisoned our own environment.

Govt. official Maeda Tadashi: “Hey, it’s no big deal. If we don’t sell nuclear power, someone else will, anyway.” (photo from Asahi Shinbun)

Worse yet, Maeda Tadashi, an official at the “Japan Bank of International Cooperation”, has rationalized Japan’s actions in Vietnam by saying, “They’ll just buy from another country” if we don’t sell them nuclear power. Send that man back to elementary school, where Japanese students study “Morality” (Dotoku)! I would zap my own son instantly (and effectively) with the Scornful Glare of the Righteous Mother if he ever dared to use such a snivelling excuse! Poor Mrs. Maeda, both the wife (if he is married) and the mother (if she is still alive).

As for the officials enthusiastically promoting the nuclear power plant in Vietnam, we must hope that they have the decency to put the safety of their own citizens above the lure of profit and economic development. Journalist Kimura-san sees it as a dual responsibility and a grave one, as Japan, “….which painfully experienced the danger of nuclear power and is still unable to resolve the pain, is not sufficiently conveying that pain to the country which is for the first time planning to use nuclear power. I wonder how much the presence of the residents is within the consciousness of the planners [in Vietnam] and whether these people, who are to be placed at the front line of a national enterprise, will be protected.” Well-considered, and well-said.

Residents of Fukushima were not protected, in the end, and citizens across the country continue to feel a deep sense of betrayal by the government. Yet before 3/11, we too were complacent, and believed in (or allowed ourselves to be deceived by ) the myth of safety. Is it any wonder that we want to warn the citizens of Tay Anh?

Good night, and thank you again for reading. I hope it won’t be another month before I can post again, but bear with me if that’s the case. Please rest assured, anyhow, that a long silence does not mean I have jumped ship; I plan to stay on board for the whole journey. Stay with me.